GK3: Budapesht Mon Amour

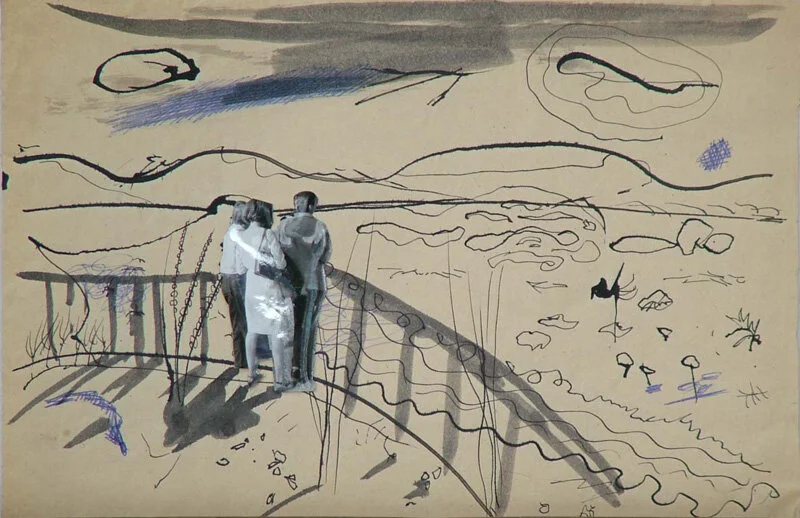

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film Nights on the Boulevard, 1972, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, watercolour and pencil on paper

September 2019

Magyar settlements existed along the banks of the Danube dating back to the late 9th century, but the first bridge between Buda and Pesht was only built in 1873. Prior to that the towns were largely two separate entities. Crossings occurred rarely and with difficulty, as a result the character of the two towns remained quite distinct. Buda was, and still is, very hilly and green. Back then it was also mainly German speaking, Catholic and loyal to the Austrian Habsburgs. Pesht was, and still is, flat, urban/e and not-so-very-green. It was also mainly Hungarian speaking, heavily Protestant and Jewish, loyal to the Magyar cause for independence and left-wing. Many on either side of the river opposed the unification and mistrusted those across the Danube. Nevertheless unification went ahead and half a dozen more bridges followed the construction of the Széchenyi Chain Bridge. In 1873, after nearly a thousand years of continuous settlement, the two ancient towns became a city. Now, before I get to GK, a quick word on Budapesht. Budapesht is in fact the correct Hungarian pronunciation, but the Hungarians write it just as we do. I’m going to leave that “sh” in though because it sounds authentic, and has such a nice purr to it...

György Kovásznai was born in Pesht on May 15, 1934. He lived all his days in the city until his death in 1983 at the age of 49. The city he grew up in was a bombed out wreck, the result of the Siege of Budapest which took place between December 1944 and February 1945. The siege was a 50 day stranglehold by the Soviets who eventually took the city, and kept it for the next 44 years. Budapest lay in ruins.* 80% of the buildings were destroyed or damaged, including beautiful historical buildings like the Parliament and the Castle. All seven bridges spanning the Danube were destroyed. It would take decades for the city to be re-built.

Robert Capa, Elizabeth Bridge Destroyed, Budapest 1948, © Robert Capa

Laszlo Fejes, Wedding, Budapest, 1965, © Laszlo Fejes

In the early ‘60s the bloody anti-Soviet uprising of 1956 and its repressive aftermath was slowly giving way to what would become known as Goulash Communism. In order to appease the population János Kádár - one of the longest serving dictators of the Communist era – introduced a degree of reform. A limited number of private businesses were allowed to operate, a greater variety of consumer goods were allowed into the country, as well as a small degree of cultural freedom. All of this was just enough to stimulate the economy and keep people quiet, (most people that is), and to allow them to let off steam without starting another revolution. One of the more surprising results of these reforms was that Hungary, and Budapesht in particular, acquired a reputation for being “the merriest barracks in the Bloc”. It was still grey compared to gai Paris, but it was positively technicoloured compared to Bucharest and Białystok.

GK made many films about Budapesht, some where the city itself is the protagonist, some where the city takes a backseat to character and story. All of these films are a testament to the life of the city that continued to evolve and thrive despite the repressive nature of the regime. There are certain leitmotifs to which GK returned repeatedly in these films, one is the river and its bridges, the other are its cafés and the characters that frequented them. Throughout he uses paintings from his Danube Riverbank and Pressó (Café) series. These vibrantly coloured, loose-wristed paintings are neither classical/realist nor avant-garde, for GK was not interested in belonging to groups or writing manifestos. He wanted to document moments in paint and to conjure the spirit of time and place. As for the citizens of Budapesht, they share an equal starring role with the city in his films. In “Diary”, the students exude youthful exuberance and its attendant confusions. In “The City Through My Eyes” GK pushes the documentary envelope with multiple scenes of live action. “Nights on the Boulevard” is resplendent with bar flies, bohemians, lonely hearts, lovers and café tragics. “Memories of the Summer of ‘74” teems with screaming tykes running through parks and splashing in pools. The city’s wry, sardonic spirit remains omnipresent, its river and bridges a constant reminder of humanity’s borderless spirit. I will proceed chronologically from here, from 1966-1974. I hope you enjoy watching the films as much as I have writing about them.

“Diary” (1966)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1RAeSQNV90Q&t=53s

Do you remember being 20? Or maybe you still are 20, or yet to turn 20… When I think of being 20 the days felt long and time felt fluid. I had so little to do and so much time in which to do it. Whole days passed just rolling from one place to the next with friends. “Diary” is a bit like that. It’s a snapshot of a day in the life of three university students killing time in town together. It’s dated August 30 1966, summer’s end. The friends also form a fraught little love triangle (can love triangles ever be anything but fraught?), whose tension builds as the day grows long. The narrative heart of this film is driven by the chapter titles, ten parts in all, starting with “Our Endless Loafing” and closing with “Then She Left Us”. However conventional, linear storytelling takes a backseat to the evocation of place and spirit. GK achieves this through his idiosyncratic combinations of documentary elements (live action, still photography) with his paintings, watercolours and line drawings. As always music plays a crucial role. The opening song by the Illés band sets the tone with its upbeat rhythm and its lyrics so suited to the random ramblings of the kids through the streets:

“I stop on the street corner, where to next? No idea.

I take a few steps this way, that, hey, why should I go anywhere?”

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film, Diary, 1966, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai

The ambient sounds of the city are especially evocative as GK drops them in at key moments: rain, cars and rattling trains are all used to great effect. In the end the consolation prize for the boys is the river itself. GK presents his Danube paintings as we might have seen them in an exhibition, if he had been allowed to exhibit his work (https://www.nicolewaldner.com/poetic-boost/2019/3/27/gk1-kovsznai-did-not-exist).

“The City Through My Eyes” (1971)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enPNbBYlDcY&t=46s

The film opens with sweeping panoramic shots of the Danube and its bridges. It’s dawn, there’s birdsong, an almost pre-historic fog cloaks the city in possibility. This film is another day in the life story, only less personal, more of an homage to the city itself. Just as GK has us soaring loftily over the capital he brings us right back down to earth, to the reality of rush hour commuters cramming into trams. There are wonderfully candid portraits of people walking down the ring road that reveal much about the life of the city, its social mores and how they’ve changed. The girls only sometimes look up at the camera and when they do it might be shyly, or coyly, the on-screen kisses are demure, there’s frankly less flesh on display. It’s warm and sunny, but practically nobody is wearing sunglasses, and the total absence of gadgets makes them seem far more removed in time from us than they really are. GK’s documentary footage of the citizens of Pesht is inter-cut with his painted portraits of them. The river is once more a major presence. GK evokes its peace and beauty both through live action and painting. We see silhouetted figures standing by the apartment windows that line the Danube, some in house-coats, drawing back sheer curtains to reveal the great river, Europe’s second longest after the Volga. A river that flows through ten countries, originating in Germany in the west, and emptying into the Black Sea in south-east Romania.

Gyorgy Kovasznai, Danube Riverbank series, 1965-1974, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, mixed technique on paper

Gyorgy Kovasznai, Danube Riverbank series, 1965-1974, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, mixed technique on paper

“Nights on the Boulevard” (1972)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNw3d55BjRs&t=24s

The film opens with this quote by the famous Hungarian poet and writer Dezső Kosztolányi (1885-1936) from his short stories “Kornél Esti”:

**“Budapest! I lived here! Among spirits! All soul! All flesh! Coffee houses! Ecstasy! Wondrous night gone down in flames!”

GK was a regular of the Pesht bars and cafés featured in this film, which so beautifully evokes the meeting places of the intelligentsia in the city. But GK is at pains to emphasise that intellectuals and non-intellectuals alike gathered in these places and he does so by using snippets of dialogue from the characters that populate his painted cafés, dialogue that is most often humorous and a little absurd too. Yet from the opening frame a bohemian spirit roams through the café, his sky blue scarf trails behind him, the ends of which spell out his name: Poeta. It is Kosztolányi’s spirit that trembles and sways through this film, clutching his unpublished manuscript, his “Wreath Sonnet”, searching in vain for the poetry editor.

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film Nights on the Boulevard, 1972, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, watercolour and pencil on paper

The roots of Central Europe’s café culture run deep, beginning in 1683 when the first coffee house opened in Vienna. From there it spread quickly to Budapest as did the unique atmosphere of the coffee houses which were fuelled by caffeine’s black gifts. By the late 19th century, when many of the grand cafes featured in GK’s film were built, they had become the favoured meeting places of artists and intellectuals. WWI and WWII radically altered the nature of coffee house life not just because enjoying oneself too much in public was frowned upon, but because those magic black beans were so hard to come by. In GK’s student days in the ‘50s, post-war shortages still existed and it was not uncommon for coffee grounds to be re-used. Those who did not wish to drink dregs knew to slip a one forint note into the waitress’ order pad, or else bring the barista a pair of nylon stockings from Vienna, or a nice bar of Fa soap. By the time “Nights on the Boulevard” was made in 1972 good coffee was readily available and café life in the merriest barracks in the bloc was in full swing once more.

The café backgrounds in the film were drawn by a number of different crew members sitting around making sketches in the most famous boulevard cafés - The Luxor, The Baross, The Centrál, The New York - some time in the early ‘70s , hence their rather eclectic feel. The first two cafés no longer exist, and the second two have been restored not to their former glory, but transformed into something they never were. To places that evoke but eschew history, places with hard, glinting surfaces that reflect not the past, but a brash new present of big money, strained glamour and tourist fantasies about ye goode olde days in Pesht. (Sorry, I couldn’t resist the anti-plug.) The characters in the film were drawn by the maestro himself and they positively brim and thrum with life, humour, affection and authentic detail.

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film Nights on the Boulevard, 1972, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, watercolour and pencil on paper

The spirit of another writer also permeates this film, and that is Gyula Krúdy (1878-1933), one of GK’s favourite writers. In ***“Life Is A Dream”, Krúdy’s last stories, self-published in December 1931, he describes in rich, surreal detail an era of career waiters, of little restaurants in courtyards that only the locals knew about because they were on dark side streets named after forgotten mayors, of a time when customers had to stick a cigarette behind the barman’s ear to get a fresh mug of beer and not the diluted dregs... Oh, that word again! Beware the naïve tourist in Budapesht!

As the chorus of the hit song from GK’s day “Alone” rings out, a truth about the enduring appeal of the coffee house is distilled:

“I’ve got to tell you something, I’ve got to admit something,

I can’t live alone, not me.”

“Nights on the Boulevard” unfolds through a cumulus of cigarette smoke, both bustling and intimate, familiar but with a tremor of unspoken possibility under cover of starry night. Spoiler alert! The ending of this film is a glorious triumph of poetry over prose!

“Memories of the Summer of ‘74” (1974)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PW7BtfDplo8

As the title suggests this film is about memories, as such it is rather abstract and free form, defined not by narrative structure but by sensual impressions expressed through the transformations of paintings to the rhythm of music. In this respect it is like “Wavelengths” which I wrote about in GK2 (https://www.nicolewaldner.com/poetic-boost/2019/6/25/gk2-creative-fury). Both films take an idea - here memories of the summer of ’74, there sounds from the radio - and riff on it, teasing out the emotional responses. The release and joy of summer are celebrated in the many parks, outdoor pools and cafés of the city which teem with energy. Daily life in Budapesht is once again conjured in paint, with accuracy, affection and a documentary eye for detail.

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film Memories of the Summer of ‘74, 1974, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, watercolour and pencil on paper

Gyorgy Kovasznai, still from the animated film Memories of the Summer of ‘74, 1974, © Estate of Gyorgy Kovasznai, watercolour and pencil on paper

The film also comprises a major collection of GK’s watercolours, 56 in all. He incorporated these watercolours into the film using cel animation, placing the celluloid sheets over the watercolours, painting, re-painting and moving the cels to give the sense of dynamic movement which so beautifully conjures the gaiety of summer. But summer must inevitably end and the film closes on a melancholy, almost sombre autumnal note. It is a feeling of which we know little here in the sub-tropics, where autumn slips in with a scarcely noticed shrug, only the odd deciduous tree signalling its return. Throughout GK’s paintbrush moves to the beat of the rhythm, to the pulse of the city, to the ticking of his rigorous mind and the riverwind of his spirit. ◊

I will be concluding my series on the amazing György Kovásznai next quarter with an essay about his 1976 animated television series on fashion called “It’s Just Fashion: A Musical and Dancing Picture Book on the Fashions of Yesteryear”. Never one for cliché or banality, GK’s take on fashion is unlike anything we’re likely to see anytime soon on our screens. See you then!

*The black and white photographs included in this essay come from a superb exhibition entitled: ”Eyewitness: Hungarian Photography in the Twentieth Century. Brassaï, Capa, Kertész, Moholy-Nagy, Munkácsi”, Royal Academy of Arts, London, June 30-October 2, 2011.

**BTW Kosztolányi’s brilliant novel “Skylark” is available through NYRB Classics (New York, 2010). It tells the story of an aging couple who re-discover life when their only child, the spinster Skylark, goes away on holiday.

***”Life is a Dream” by Gyula Krúdy, Penguin Classics (2010), translated by John Batki, from their series entitled Central European Classics.